Executive Summary:

- The period of globalization following World War II brought great economic prosperity and raised the standard of living in many parts of the world.

- However, globalization appears to be reversing course to some degree, changing the dynamic of the relationship between countries like the US and China from one of coordination to competition.

- Given the diametrically opposed philosophies underpinning the two superpowers, (e.g., individualism versus collectivism), and the power that rapidly advancing technologies like artificial intelligence creates, this competition could have profound implications for geopolitics for decades.

- Although we expect competition to intensify going forward, we believe sufficient deterrents exist currently to make the likelihood of conflict low.

We begin this note with a quote, one that has been attributed to so many sources that it is difficult to pinpoint who said it first (so we’re giving three people credit).

“There are no permanent friends and no permanent enemies, only permanent interests.”

William Clay or Henry Kissinger or Lord Palmerston

Globalization is a broad term that describes the increasing interconnectedness of the world through trade, technology, and the sharing of ideas and cultures. While there is general agreement on the concept, there is great debate regarding when globalization officially began. Was the Silk Road, the ancient trade route of two millennia ago, the beginning of globalization? Or did Columbus reaching the “New World” in 1492 mark the emergence of the global village?1 For this note, we are going to leave that debate to historians and confine ourselves to the post‐World War II era.

The Bretton Woods conference, which included delegates from the 44 World War II Allied nations, took place in New Hampshire in 1944. This conference resulted in the establishment of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to promote the stability of exchange rates and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) to aid in post‐war reconstruction and economic development. The US Treasury Secretary at the time, Henry Morgenthau, stated that the establishment of the IMF and the IBRD marked the end of economic nationalism.2 In this way, the Bretton Woods conference laid the foundation for the global open market system that we think of today.

Another important milepost in this most recent iteration of globalization occurred in 1979 when the US and China normalized trade relations. At the same time the Chinese government, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, allowed private industry to develop and began embracing free markets. The result was a multi‐decade period of global coordination supported by shared interests. Many Western democratic countries found that they were able to reduce costs by outsourcing labor and manufacturing to China and by tapping into their enormous and growing consumer base. However, China may have benefited to an even larger degree, growing its economy five‐fold since 2001 (when it entered the World Trade Organization) and lifting hundreds of millions of people from extreme poverty.3

In the same way that the beginning of globalization is open to debate, whether globalization is now reversing its course is also an open question. Regardless of your opinion on globalization writ large, it appears that the multi‐decade period of coordination between the incumbent superpower, the US, and the emerging superpower, China, has officially ended. The mutually beneficial arrangement that strengthened both economically has given way to fierce competition, laying bare an important lesson related to the opening quote of this note – the past few decades of coordination appear to have only marked a temporary, rather than a permanent, alignment of interests.

Although spy balloons and the “no limit” friendship with Russia have been in the headlines recently, bad blood between the two countries has slowly been building for years. Allegations of intellectual property theft, human rights allegations related to the Uighur population, accusations that Tik Tok and other Chinese apps are being used to spy on US citizens, calls to onshore supply chains for critical items – US politicians, businesses, and media have been railing against the threat China poses to free markets for years. The US CHIPS and Science Act, passed with bipartisan support late last year in an effort to bolster domestic technology production, illustrates that opposition to China seems to be one of the last few issues that can bridge the vast US political divide.

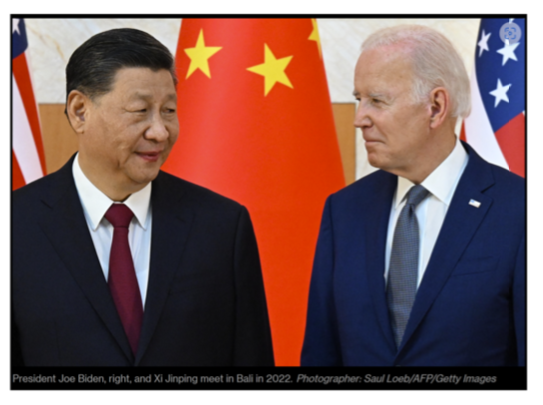

The criticism flows both ways, as well, with China calling out and criticizing the US publicly more often. For example, China has pointed the finger at the US and its “radical fiscal policy” for the economic woes of some of the poorest countries in the world.4 China has also sought to supplant the US in the peacemaker role on the world stage of late, trying to repair the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia and offering a ceasefire proposal for the Russia‐Ukraine war. It is in China’s best interest to paint itself as an ascendant country interested in promoting global peace while making the US appear to be the opposite, a fading global power that wants the conflict to continue.5 Yet even more concerning, both Chinese President Xi Jinping and Foreign Minister Qin Gang have recently been quoted as saying the US has been engaging in the suppression and containment of China and that the US needs to change its attitude toward China quickly or “conflict and confrontation” will be inevitable.6 7

Given the clash of cultures, it should be no surprise that open competition between the US and China has finally arisen. The stakes of this competition in today’s world are quite high, though, as illustrated by the following quote by Wisconsin US House Representative, Republican Michael Gallagher

“This is an existential struggle over what life will look like in the 21st century—and the most fundamental freedoms are at stake,”8

There are two areas that we believe best illustrate the current level of competition – semiconductors and artificial intelligence. Semiconductors have essentially become the lifeblood of the global economy in recent years. In the “Internet of Everything” environment in which we live, semiconductors are found in computers, smartphones, speakers, automobiles, kitchen appliances, advanced defense systems – nearly everything that requires electricity. Unfortunately, the US only accounts for about 12 percent of global semiconductor capacity currently. This vulnerability became abundantly apparent during the pandemic when global semiconductor supply chain issues caused a shortage of chips required for automobiles. As a result, supply fell and drove the cost of both new and used vehicles up significantly in the US. The US CHIPS and Science Act was passed in part to address this vulnerability and to make the US a leader in the semiconductors industry again.9

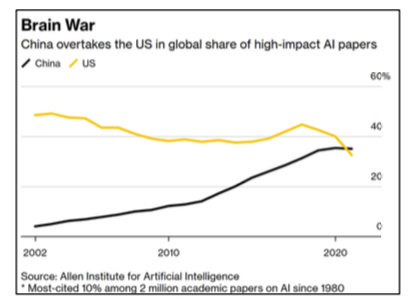

Another related area of fierce competition is artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Hype related to new technologies is nothing new and people have been talking about the potential power of AI for decades (remember, IBM’s Deep Blue beat World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov back in 1997). Nevertheless, we may be at the tipping point for AI, when it turns from a promise into a day‐to‐day reality.

When asked in a recent interview about the biggest risks in 2023, Ian Bremmer, founder of political risk consulting firm Eurasia Group, said AI is possibly both the biggest risk and opportunity.

He believes 2023 is the year AI passes the Turing test, meaning consumers will no longer be able to differentiate between answers generated by humans and those created by bots. The opportunity this moment presents is that consumers will have unprecedented access to intelligence, not just data. On the other hand, the risk of generative AI is that it will be easier than ever to create more compelling disinformation and threaten the very functioning of society.10 If Bremmer’s assessment of the power of AI is accurate, becoming a global leader in AI is crucial for both countries, to drive greater economic growth and defend against efforts to destabilize government by competitors. In short, the AI race is one neither the US nor China can afford to lose.

This competition for economic and technological supremacy isn’t just a cold war of words; it also manifests itself in a physical place – Taiwan.

This island, located just off the coast of China, has been the focus of great geopolitical debate related to its political status. Taiwan is claimed by The People’s Republic of China (i.e., China) as its own, but Taiwan (officially called the Republic of China) is officially recognized by 12 of the 193 United Nations countries and its citizens are split between pro‐ independence and pro‐unification factions. The debate regarding whether it is part of China, or its own independent country has taken on even more significance of late, as Taiwan has become the global leader in advanced semiconductors. Given the importance of advanced semiconductors to the global economy and the advancement of AI, Taiwan finds itself in a precarious position – balancing between two opposing superpowers intent on being the world’s sole technology leader.11

While the increase in tensions and rhetoric recently may be disconcerting, it is important to remember that in a world of nuclear weapons and mutually assured destruction, rationality demands military restraint. Competition can last for decades or even centuries, and it does not make conflict inevitable. As NATO allies have proven with Russia post‐invasion, economic sanctions and isolation can quickly make an aggressor nation a pariah in today’s globalized market. Time will tell if this phenomenon persists in the future if globalization gives way to greater onshoring and nationalism, but we believe it is a powerful deterrent for both sides today.

“May you live in interesting times”

Unknown12

This quote, which is frequently claimed as a Chinese curse (although no source has been identified), seems an appropriate place to leave this note. The irony of the statement is self‐evident upon reflection; quiet and uninteresting times tend to be most peaceful, while history‐making periods tend to correspond with competition, conquest, and conflict. While things have certainly gotten more “interesting” of late, competition thus far between the US and China has taken the form of technological advancement and economic sanctions rather than military engagement. We anticipate the trend toward increased competition to continue.

As always, geopolitics plays an important role in how we think about allocating risk on your behalf. Please reach out if you would like to schedule a time to review your specific situation.

1 Source: Globalization (nationalgeographic.org)

2 Source: Bretton Woods Conference ‐ Wikipedia

3 Source: The Contentious U.S.‐China Trade Relationship | Council on Foreign Relations (cfr.org)

4 Source: China Blames US’s ‘Radical Fiscal Policy’ for Poor Countries Debt Troubles ‐ Bloomberg

5 Source: After Xi’s Russia Trip, US Fears World May Embrace China’s Ukraine Peace Bid ‐ Bloomberg

6 Source: China says U.S. should change attitude or risk conflict | Reuters

7 Source: China’s Xi Jinping Takes Rare Direct Aim at U.S. in Speech ‐ WSJ

8 Source: U.S., China Plunge Further Into a Spiral of Hostility ‐ WSJ

9 Source: What Is The Semiconductor CHIPS Act, And Why Does The U.S. Need It? (forbes.com)

10 Source: Episode 1: Should I STILL be worried? (gzeromedia.com)

Past performance may not be representative of future results. All investments are subject to loss. Forecasts regarding the market or economy are subject to a wide range of possible outcomes. The views presented in this market update may prove to be inaccurate for a variety of factors. These views are as of the date listed above and are subject to change based on changes in fundamental economic or market-related data. Please contact your Advisor in order to complete an updated risk assessment to ensure that your investment allocation is appropriate.